CAW (part 3): Live Coding with CAW

CAW is a Rust library for making synthesizers. This post is about using CAW to perform music live by writing code into a Jupyter notebook.

Previous posts about CAW:

Live coding is a type of performance where music (or other art) is generated in real time by writing and evaluating code. Dedicated programming languages exist for live coding, such as Tidal Cycles, and performers usually write code in an editor that’s tightly integrated into the evaluation of the program. If your program is generating music you want to be able to change the program and have the change take effect without needing to restart the program.

The standard workflow for programming in Rust is to write code, then compile the code, then run the resulting executable. If you change the code you need to restart the executable for the change to become visible. The project evcxr implements a Rust REPL where programs can be evaluated line by line, and a Rust Jupyter Kernel allowing Rust to be written into a Jupyter notebook. Code in one cell can be rerun without needing to restart the entire program.

We need to approach defining synthesizers a little differently when writing them in Jupyter. Take this simple program as an example which plays a sawtooth wave sweeping between 100Hz and 150Hz:

use caw::prelude::*;

fn signal() -> Sig<impl SigT<Item = f32>> {

let lfo = oscillator(Saw, 0.5).build().signed_to_01();

oscillator(Saw, 100.0 + (lfo * 50.0)).build()

}

fn main() {

let player = Player::new().unwrap();

let _handle = player.play_mono(signal(), Default::default()).unwrap();

std::thread::park();

}

The standard way of writing CAW synthesizers is to create a top level signal

(usually by composing simpler signals) and then play it on a Player.

We could start by just copying this program into Jupyter:

// Cell 0:

:dep caw = { path = "/path/to/caw/source", features = ["player"] }

// Cell 1:

use caw::prelude::*;

// Cell 2:

fn signal() -> Sig<impl SigT<Item = f32>> {

let lfo = oscillator(Saw, 0.5).build().signed_to_01();

oscillator(Saw, 100.0 + (lfo * 5.0)).build()

}

fn main() {

let player = Player::new().unwrap();

let _handle = player.play_mono(signal(), Default::default()).unwrap();

std::thread::park();

}

main();

Note the first cell where we tell evcxr about the notebook’s external dependencies.

Also note the call to main(). Jupyter doesn’t automatically call the main function, but allows

code to be written outside of functions which is run when the containing cell is evaluated.

With that in mind we can get rid of the entire main function and put its contents in the top level.

This also lets us get rid of the std::thread::park() previously required to stop main() from returning

immediately. The handle returned by player.play_mono(...) stays in scope in the notebook forever

so the sound will keep playing until the kernel is stopped.

// ...

// Cell 2:

fn signal() -> Sig<impl SigT<Item = f32>> {

let lfo = oscillator(Saw, 0.5).build().signed_to_01();

oscillator(Saw, 100.0 + (lfo * 50.0)).build()

}

let player = Player::new().unwrap();

let _handle = player.play_mono(signal(), Default::default()).unwrap();

This runs and we hear the frequency sweep. Say we want to change the base frequency from 100Hz to 200Hz. If you update the code accordingly and the rerun the cell, not only will the base frequency change but the sweep will reset to its start position. The entire state of the program has been reset. This isn’t ideal because if you’re generating a looping melody and you change some aspect of the melody, applying the change will cause the melody to restart from the beginning of the loop. You could try to synchronize your changes with the start of the loop, but let’s find a better way to update running synthesizers without resetting their state.

First, a false start: Split the cell into two cells.

// ...

// Cell 2:

fn signal() -> Sig<impl SigT<Item = f32>> {

let lfo = oscillator(Saw, 0.5).build().signed_to_01();

oscillator(Saw, 100.0 + (lfo * 50.0)).build()

}

// Cell 3:

let player = Player::new().unwrap();

let _handle = player.play_mono(signal(), Default::default()).unwrap();

This might seem like it would fix the problem. The player is now only created once,

and updating the cell containing the definition of signal doesn’t cause the signal

to be recreated. Unfortunately that’s exactly the reason why updating the signal function

and re-evaluating its cell has no effect! All we’ve done is redefine the function, but

it hasn’t been called yet, so nothing happens to the sound.

Instead we need a way of reaching into a signal and changing a value without

redefining or restarting the signal. To make this possible, CAW introduces a

new collection of types called Cells. A Cell is a container which can store

a signal (an implementation of the SigT trait) inside it. A Cell is also

a signal, and it acts like the signal it contains, and has some extra methods

to allow replacing the stored signal with some new signal.

To allow the base frequency of the sweep to be dynamically changed, we’ll replace the static 100.0

in the code with a Cell defined globally, and then change the Cell’s value once the program

starts running. Rust functions aren’t allowed to access variables defined in

external scopes (only constants and other functions), so we first need to take a

little detour to change the way the signal is defined. One option might be to just define the

signal globally rather than with a function, however a limitation of evcxr is that

type inference for global variables seems to struggle with functions returning impl <Trait>

which is very common in CAW. We could explicitly state the type:

let lfo: ... = oscillator(Saw, 0.5).build().signed_to_01();

let signal: ... = oscillator(Saw, 100.0 + (lfo * 50.0)).build();

…however unboxed signals tend to have very long types that reflect the types of all the simpler signals they are composed of. For example the type of lfo is:

Sig<SignedTo01<Oscillator<Saw, f32, f32, f32, bool>>>

and the type of signal:

Sig<Oscillator<Saw, Sig<OpScalarSig<f32, OpSigScalar<SignedTo01<Oscillator<Saw, f32, f32, f32, bool>>, f32>>>, f32, f32, bool>>

Instead, let’s define the signal with a closure and capture the Cell variable

storing the base frequency. While we’re at it, let’s change how the player is

created to be more ergonomic for notebook programming. CAW has a live_stereo function

which creates a player and returns a Cell whose contents will be played. We can

update its contents with a signal to play that signal, and then later update its contents

with the signal 0.0 to silence the player. That way we no longer have to stop the entire

notebook to make the sound stop!

One change at a time. First, here’s the notebook refactored to use live_stereo:

// Cell 0:

:dep caw = { path = "/path/to/caw/source", features = ["live"] }

// Cell 1:

use caw::prelude::*;

// Cell 2:

let out = live_stereo();

// Cell 3:

out.set(|| {

let lfo = oscillator(Saw, 0.5).build().signed_to_01();

oscillator(Saw, 100.0 + (lfo * 50.0)).build()

});

Then to replace the output signal with silence, run:

out.set(|| 0.0);

This uses the “live” feature which enables the live_stereo function.

Notice how the set method takes a closure which returns a signal rather than just a signal.

That’s because out is actually a pair of Cells corresponding to the left and right audio

channels. The set method calls the closure twice and sets the left and right Cell to the result

of the respective calls (there’s also a set_channel method which passes the channel to the

closure for more control over stereo audio).

Now, to allow changing the base frequency of the sweep, update the definition of the sweep

to use a Cell for the base frequency:

// Cell 3:

let base_freq_hz = cell(100.0);

out.set(|| {

let lfo = oscillator(Saw, 0.5).build().signed_to_01();

oscillator(Saw, base_freq_hz.clone() + (lfo * 50.0)).build()

});

Now in a later cell, update the base_freq_hz value:

base_freq_hz.set(200.0);

…and the base frequency will change without affecting the timing of the sweep itself.

This time set just takes a signal, since base_freq_hz is a regular Cell.

Cells can contain arbitrary signals - not just constant values - so we

could do something like:

base_freq_hz.set(100. + oscillator(Sine, 8.0).build() * 10.0);

…so that the base frequency is modulated by another low-frequency oscillator.

Or we could open a window with a knob allowing the base frequency to be tuned manually. To enable this, update the dependencies in the first cell:

// Cell 0:

:dep caw = { path = "/path/to/caw/source", features = ["live", "widgets"] }

Then run:

base_freq_hz.set(knob("base freq").build() * 100.0);

Knobs by default yield values between 0 and 1, so multiply the knob by 100 to allow tuning frequencies between 0Hz and 100Hz.

Cells are how CAW allows synthesizer configurations to be dynamically changed in a running

notebook without resetting the synthesizer’s state. They require some planning when defining

signals, as all the Cells a signal will use must be declared ahead of time, and the broader

structure of a signal still can’t be changed without resetting its state. Despite these constraints,

I’m still amazed that this works at all! I think of Rust as a static language with a big conceptual

gap between the code you write and the program that runs, and being able to change parts of a program

while the rest of the program continues running is awesome.

CAW’s visualizations work in notebooks! To view a visualization of the waveform, update the cell with live_stereo() to:

// Cell 1:

let out = live_stereo_viz_udp(Default::default());

…and restart the notebook.

The function live_stereo_viz_udp gives a hint about how the visualization works.

CAW uses SDL2 for its visualization, and SDL2 needs to run from the main thread of the program.

There’s no way to satisfy that constraint when opening a window from a notebook, so the only

way to have the notebook open a window is if it runs a new process and have that process use SDL2

to render the visualization on its main thread. But this means CAW running in the notebook needs to

be able to send the data to visualize to the new process, and CAW sends this data over a UDP socket.

While often used for communication across computer networks, UDP works just fine as an inter-process communication protocol, and thanks to its ubiquity as a transport layer protocol for the internet, it’s implemented everywhere; I don’t need to find a separate IPC mechanism for Windows vs Unix machines.

Knobs are also rendered with SDL2 and each knob is a separate process which communicates with the CAW process by sending MIDI commands over UDP sockets. I didn’t realize this at the time but it’s actually quite common to use UDP as a transport protocol for synthesizer software and hardware.

To use visualizations and widgets you’ll need to have a pair of programs installed somewhere in your

PATH: caw_viz_udp_app and caw_midi_udp_widgets_app.

E.g., run:

$ cargo install caw_viz_udp_app caw_midi_udp_widgets_app

These are the programs that CAW will run when opening visualization or knob windows.

There’s a Nix project here that

sets up all the necessary dependencies for using CAW in a Jupyter notebook. You’ll

also need a local checkout of CAW itself to point to

intead of "/path/to/caw/source" in the code snippets on this page.

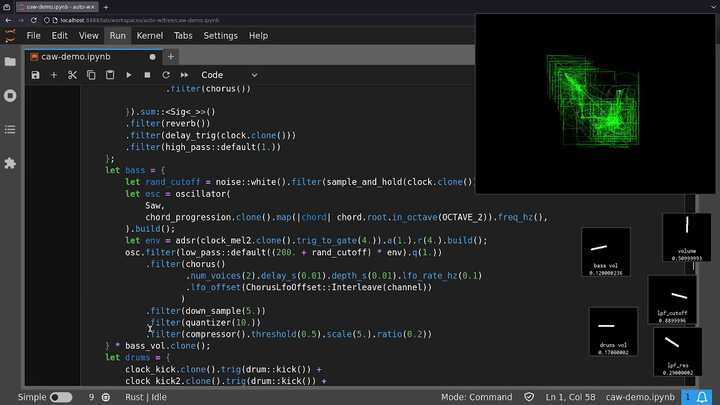

Here’s a video of a jam session with CAW in a Jupyter notebook: