CAW (part 2)

CAW is a Rust library for making synthesizers. See Part 1 for the basic idea.

I started noticing performance limitations where input latency was frustratingly high when playing live music with CAW, and complex patches would cause the audio to start crackling, indicating the program couldn’t keep up with the sound card’s sample rate. I was aware of some design decisions I made for the sake of convenience which I expected to have a performance impact. This post is about how I rewrote CAW to speed it up.

Why was CAW slow?

There were two aspects of CAW’s original design I suspected were slowing it down. Firstly there’s the fact that each sample was being fully computed one at a time. CAW synthesizers are made by composing modules, and each module typically has some input signals, and produce some output signals. For example a low-pass filter takes an input audio signal and an input signal controlling the filter cutoff, and produces an audio signal which is the input audio with the filter applied. Feeding a single sample through all the modules making up the synth, and then feeding the next sample and so on meant that CAW probably wasn’t making the most of the CPU’s ability to cache recent instructions. CPUs are better at doing a series of tight loops than one really big loop. Thus I expected having modules operate on batches of samples would yield better performance. This also fit nicely with the interface between CAW and the sound driver provided by the Rust library cpal, which sends batches of samples to the driver at a time.

The second issue is that each signal was boxed in a Rc<RefCell<_>> which

was preventing the compiler from making certain optimizations. Also accessing a

signal to apply its internal logic required performing a check for exclusive

access to the RefCell<_>, which were guaranteed to always succeed anyway due

to how signals were implemented, so the checks were just wasting time.

Also speaking of exclusive access, Rc<RefCell<_>> is not safe to pass between

threads - something Rust enforces at compile time. This prevented CAW

synthesizers from being easily parallelized across multiple threads. An alternative

representation would be Arc<Mutex<_>>, however experimentally introducing

this type led to a noticeable performance hit for single-threaded synthesizers,

and still suffered from the other problems caused by boxing signals.

The SigT trait

To unbox signals, I would need to do away with the Signal<T> type, and instead

represent signals with a trait:

pub trait SigT {

type Item: Clone;

fn sample(&mut self, ctx: &SigCtx) -> impl Buf<Self::Item>;

}

I named this SigT for brevity, as type signatures can get long in Rust.

A SigT has an associated type Item which is the type of samples produced

by the signal. This is usually f32 for audio signals and bool for gate/trigger signals.

SigCtx contains information such as how many audio samples the sound driver is

currently asking for and the audio sample rate. SigTs produce their output by

returning an impl Buf<Self::Item> - that is, a type-erased implementation of the trait

Buf<Self::Item>, defined like:

pub trait Buf<T>

where

T: Clone,

{

fn iter(&self) -> impl Iterator<Item = T>;

fn clone_to_vec(&self, out: &mut Vec<T>);

fn clone_to_slice(&self, stride: usize, offset: usize, out: &mut [T]);

}

So a Buf<T> is something which can be iterated over yielding Ts, kind of

like IntoIterator but more general in that it doesn’t mandate a specific

iterator type, and more specialized with methods for efficiently copying the data

to different array types for quickly transferring their contained data to the

sound driver’s buffer.

Looking at the type of SigT::sample it might seem like

it needs to allocate a new buffer every frame, however Buf<T> is implemented for &Vec<T>.

A reference to a reusable Vec<T> is a Buf<T> which allows modules to contain their own

output buffers. The sample method usually updates the module’s internal buffer and then just

returns a reference to the buffer.

For scalar types like f32, there’s a type ConstBuf<_>:

pub struct ConstBuf<T> {

pub value: T,

pub count: usize,

}

Its implementation of Buf<T> copies the value field count many times.

This way there’s no need to allocate a buffer just to store a repeated

copy of the value of a scalar.

In addition to the SigT trait there’s also a new type Sig which wraps

implementations of SigT:

pub struct Sig<S>(pub S)

where

S: SigT;

This simplifies implementing methods for signals that are only available

for certain Item types, and making it easier to implement other traits

for signals such as those associated with arithmetic operators.

The following doesn’t work well in Rust:

// Values of any pair of types L, and R, both implementing SigT<f32>

// can be added together.

impl<L: SigT<Item=f32>, R: SigT<Item=f32>> Add<R> for L {

...

}

The problem is that it’s possible to implement SigT for a type that already

implements Add, such as f32, and Rust only allows one implementation of a trait

per type. Even the possibility that SigT could be implemented for f32 is

enough to cause problems. Generally I’ve found that blanket implementations

of a trait for all implementations of some other trait should be avoided, and instead

introduce a new type wrapping implementations of the trait, like:

impl<L: SigT<Item=f32>, R: SigT<Item=f32>> Add<Sig<R>> for Sig<L> {

...

}

It seems like it might get cumbersome wrapping every signal in the Sig type, but

the majority of signal operations are methods of Sig, not SigT, and they take

care of wrapping their results in Sig so it’s almost never necessary to explicitly

wrap values with Sig in client code.

Sharing

When composing modules with CAW, all the inputs to a module end up contained by that

module. This was true in the original implementation as well as the new one, however

originally all modules could be cloned. But unboxing signals means taking away the

Rc<_> that allowed signals to be shallow-copied and passed as input to multiple

modules. Now when you pass a signal as input to a module, it’s removed from scope

and can’t be passed to another modules.

In a way this is maybe more realistic, since you normally can’t plug multiple cables into a single jack socket (unless you use banana jacks!). And it turns out that most of the time I end up making long linear chains of signals with no sharing of a signal between modules.

But sometimes you do need to split a signal and use it in two places!

To solve this I introduced a new type SigShared:

/// A wrapper of a signal which can be shallow-cloned. Use this to split a

/// signal into two copies of itself without duplicating all the computations

/// that produced the signal. Incurs a small performance penalty as buffered

/// values must be copied from the underlying signal into each instance of the

/// shared signal.

pub struct SigShared<S>

where

S: SigT,

{

shared_cached_sig: Arc<RwLock<SigCached<S>>>,

buf: Vec<S::Item>,

}

The Sig<S> type has a method shared:

pub fn shared(self) -> Sig<SigShared<S>>

…which makes a shareable version of the signal. Note that the result is still

wrapped in Sig, and can be used in all the same ways as a regular Sig<_>

except it can now also be cloned and passed as input to multiple modules.

Input Latency

As described above, CAW is periodically presented with buffers from the sound driver which it must populate with audio samples to be played. The sound card operates at a particular sample rate, usually around 44kHz. If the program is keeping up, this means that it’s producing exactly 44000 samples each second and writing those samples into the sound driver’s buffer. The samples from a buffer don’t start playing on the speaker until the entire buffer is filled, and the larger the buffer, the longer it takes to fill. CAW’s modules batch computations over a buffer’s worth of samples, with the intuition that computing more samples in a single batch will be more efficient. So larger buffers allow CAW to compute more samples per second, but also increase the time between computing a sample and that sample reaching the speaker. It’s a latency vs throughput trade-off.

When generating music automatically, a large buffer with high latency might be ideal because latency doesn’t matter and the increased throughput means you can build a more complex sound before hitting performance issues. When playing live, you want the effect of a key press or other input to be effectively instant, so a smaller buffer is more appropriate.

CAW lets you specify a target latency, and will choose an appropriate buffer size based on the target latency and the sound card’s sample rate, bearing in mind that some sound drivers have limits on the buffer sizes they support.

Performance

I did an experiment where I played the sum of a collection of detuned sawtooth wave oscillators and kept adding more oscillators until I heard a persistent crackle indicating the program couldn’t keep up with the sound card. On my M2 Macbook Air I could originally run only ~450, and after these changes I can now run ~3000.

However, making signals into traits means that it’s possible to implement the trait in a way that can be sent between threads. Also it’s possible to compute sawtooth wave samples using SIMD instructions, so 8 different sawtooth waves can be computed in parallel within a single thread. On my 16-core AMD Ryzen machine I was able to get around 500k concurrent detuned sawtooth waves by combining these two approaches. There wasn’t enough headroom to also record the result, but here’s spooky 366600 sawtooth demo where batches of oscillators are detuned around different notes making a tritone chord:

Adding many sawtooth waves produces an interference pattern quite different from the “supersaw” effect of adding 2 to 10 or so. Sometimes many waves drift into phase with each other producing “wubs”. Here’s a less ambitious 48k concurrent sawtooth wave demo. If you click through to the youtube page, the description has a list of all the wubs with timestamps:

What’s next?

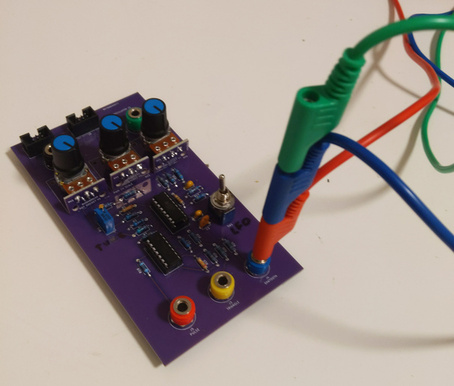

My most recent work on CAW has been focused on using it for live coding, where synthesizers can be built up and dynamically modified in a jupyter notebook with graphical UI elements for knobs and buttons.

More on that in Part 3.